I built a Docker wrapper for Claude Code and OpenAI Codex. The main reason is simple: I don't trust AI agents running loose on my machine.

Being in Cyber Security, I've developed a healthy paranoia about software that can execute arbitrary commands. AI coding assistants are powerful, but they're also unpredictable. They can run shell commands, modify files, and access the network. I wanted all of that contained.

The setup

Claudecker is my personal tool that wraps Docker to run Claude Code CLI and Codex CLI in an isolated container. Point it at any project directory and it mounts that directory into the container. The AI can do whatever it wants inside the container, but it can't touch the rest of my system.

./claudecker.sh run /path/to/project

Each run starts with a fresh environment. Skills get reinstalled, settings reset to defaults. Only authentication tokens persist across restarts. This "clean slate" approach means I don't accumulate cruft or unexpected state changes.

The paranoid feature: network lockdown

The feature I'm most pleased with is the network lockdown toggle. It uses iptables to control the container's OUTPUT chain policy.

This drops all outbound traffic except localhost and already-established connections. The AI can still work on code, but it can't phone home, download packages, or exfiltrate anything. I toggle this on when working on sensitive projects.

The implementation is straightforward. Just flipping between DROP and ACCEPT policies. The container needs NET_ADMIN capability for this to work, which is a trade-off I'm comfortable with since it's scoped to network operations.

Trade-offs from containerization

Isolation comes with friction. I had to solve several problems that wouldn't exist if I just ran the CLI directly on my host.

Browser authentication needs X11

Claude and Codex authentication use browser-based OAuth flows. Inside a container, there's no browser. I ended up mounting the X11 socket and forwarding the DISPLAY variable:

volumes:

- /tmp/.X11-unix:/tmp/.X11-unix:rw

On Linux this works if you have DISPLAY set. On macOS you need XQuartz. For headless environments, there's a fallback where I manually copy the auth.json file from a machine where you've already logged in.

Thankfully, Claude Code and Codex CLI makes it easier by providing you a URL to visit, which will give you a code to enter back. This means I rarely need to use browser authentication, but at least the option is there.

SSH agent forwarding is annoying

Getting SSH keys into the container without copying them required some workarounds. Docker's socket permissions don't always cooperate, so I ended up using socat to proxy the SSH agent socket:

sudo socat UNIX-LISTEN:/tmp/ssh-agent-forwarded,fork,mode=600,user=node \

UNIX-CONNECT:/ssh-agent &

The container tries direct socket access first, falls back to socat if that fails. Limited sudo permissions ensure the node user can only run specific commands.

Port forwarding for web apps

If you're developing a web app and want to access it from your host browser, you need to expose ports explicitly:

./claudecker.sh run --port 3000 /path/to/project

This maps the container's port to the host. Without this flag, localhost:3000 inside the container isn't reachable from outside.

Project-specific dependencies

Different projects need different tools. A C project needs gcc and cmake. A Python ML project needs different libraries. I didn't want to bloat the base image with everything.

The solution: a .claudecker file in the project directory.

# .claudecker

build-essential

cmake

gcc

python3-dev

On first run, the script hashes the file contents, generates a Dockerfile, and builds a custom image tagged with that hash. Subsequent runs use the cached image. Projects with identical .claudecker files share the same image.

claudecker-custom:a1b2c3d4e5f6

This content-based approach means I'm not rebuilding images unnecessarily, and cleanup is straightforward with clean-custom and clean-all-custom commands.

Skills system

A new and recent addition: Claudecker now supports Claude Skills, which are custom prompts that extend its capabilities. I implemented two types:

- GitHub skills get cloned on container startup. The Humanizer skill, for example, comes from a public repo and helps remove AI-isms from text.

- Local skills are baked into the Docker image. I keep these in a

local-skills/ directory.

The build process copies these into the image, and the entrypoint installs them into Claude's skills directory. This way I can version-control project-specific skills alongside the code.

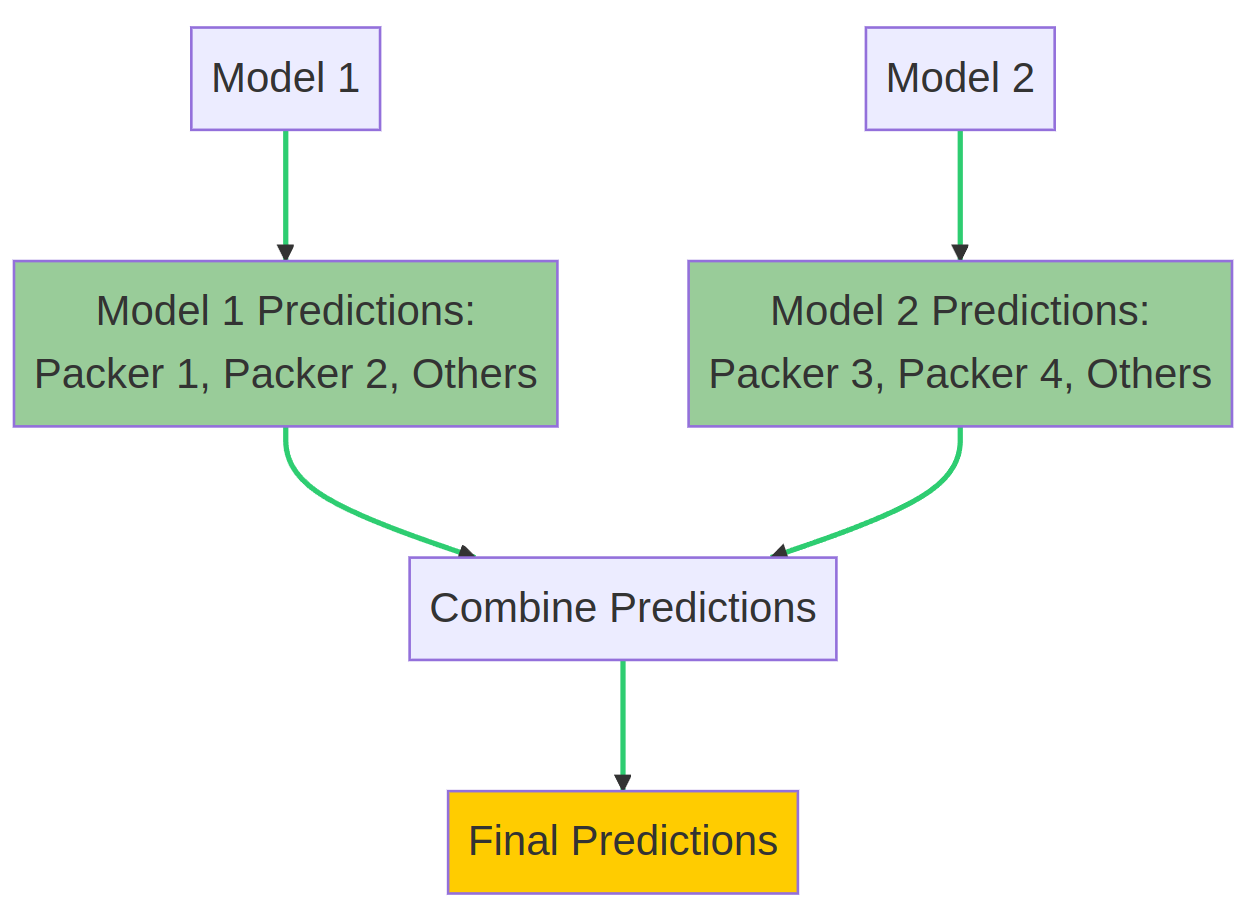

Multi-AI orchestration with PAL MCP

I also integrated PAL MCP Server, which lets Claude Code collaborate with other AI models (Gemini, GPT, Grok, local Ollama models). I export my API keys before running:

export OPENROUTER_API_KEY="your-key"

./claudecker.sh run /path/to/project

Inside Claude Code, I can ask it to use other models for second opinions, code review, or extended reasoning. The MCP server handles the routing.

This obviously requires network access, so it doesn't work in lockdown mode. Trade-offs.

Where's the code?

I planned to release this publicly but decided against it for now. There are rough edges:

- The docker-compose volumes are duplicated in the docker run command for custom images. If you change one, you have to change the other. I left a warning comment but it's still error-prone.

- The firewall whitelist script exists but isn't fully tested across different network configurations.

- Some features assume specific host setups (X11, SSH agent running, etc.) and fail ungracefully when those assumptions don't hold.

- Error handling is minimal in places.

I use this daily for my own work, but it's not polished enough for others to pick up without reading through the scripts first. Maybe later.

Current limitations

- Network lockdown state doesn't persist across container restarts. Restart the container and you're back to full network access.

- Custom image builds happen automatically but failures silently fall back to the base image. You might not notice a package didn't install.

- X11 forwarding is a security surface I'm not entirely comfortable with, but I haven't found a better solution for browser auth.

What I actually use it for

Most days I run Claude Code in lockdown mode for general coding tasks. When I need it to fetch documentation or install packages, I toggle lockdown off, let it do its thing, then toggle it back on.

For security research projects, the isolation gives me peace of mind. The AI can analyze suspicious code, suggest modifications, even run tests, all without access to my actual filesystem or network.

It's not perfect containment. Docker isn't a security boundary the way a VM is. But it's enough friction that an AI agent can't accidentally (or intentionally) do something I'd regret.

For now, this setup works for my needs. The paranoia tax is a few extra seconds on startup and occasional friction with browser auth. Worth it.